In March 2001, Dennis Tito, a US millionnaire, was an unpopular man in some corners of Nasa. Tito, an engineer by training, had offered the Russians $20m for a ride into space. That prompted an outburst from Daniel Goldin, then Nasa administrator. "We don't have time to hand-hold tourists that don't have the proper training," he raged.

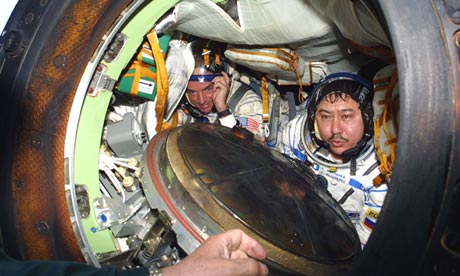

A month later, Tito blasted off on a Russian Soyuz mission and spent nearly eight days in orbit on the International Space Station. He fell around the planet, looked out the windows, and did some experiments. But what matters for the history books is that he became the world's first private space tourist.

Now Tito is back in the news. His new Inspiration Mars Foundation holds a press conference on Wednesday to launch audacious plans for a mission to Mars. The foundation's press release doesn't mention a crew, but reports in NewSpace Journal claim the mission will take two people, in a modified SpaceX Dragon capsule, launched by a Falcon Heavy rocket. What is striking about the plans is not so much the stated intention – though that in itself is ambitious – but the timescale. Tito wants to ride a slingshot mission around Mars in a window that opens in 2018. That's only five years away.

The reaction from the space community has ranged from bemusement and disbelief to encouragement and awe. "Even if this was Nasa saying it was sending a crew to Mars, I would be amazed if they thought they could pull it off so soon. But we are talking about a private individual," says Kevin Fong, director of the Centre for Space Medicine at UCL, and author of the book Extremes: Life, Death and the Limits of the Human Body, which is published next month.

But Tito is no crank. And nor are the people he is working with. One is Jonathan Clark, a former Nasa flight surgeon and now a space medicine adviser at the National Space Medicine Biomedical Research Institute in Houston. The pedigree of the team matters, and has forced the rest of the space community to take the plans seriously. Or at least more seriously than they might have. "These aren't people who've done nothing more than read a few copies of Dan Dare in the 1950s," says Fong.

John Logsdon, former director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, says he doesn't know what to make of Tito's potential announcement, as too many details are missing. But he cautions against dismissing Tito. "One thing to remember," he told the Guardian, "when Tito first planned to go to Mir as a fare-paying person, there was almost universal dismissal of the idea, but he did it. So I think a high degree of scepticism is warranted, but not yet a judgement of impossibility."

So how plausible is the mission? The journey aims to take advantage of the close alignment of Earth and Mars in 2018 to make the mission as swift as possible. But even then, a round trip will take around 500 days. That's a long time to spend in a small space capsule.

We can break the mission down into separate elements and look at each in turn. First up, fuel and energy: can a manned rocket make a round trip to Mars? The answer is almost certainly yes. As Fong points out, it takes more energy to get from Earth to low Earth orbit, than from there out to Mars. Other challenges are not so easily dismissed.

The body adapts to space. No longer burdened by its weight, the muscles that support us on Earth weaken and waste. The heart doesn't have to work as hard to push blood to the brain, so it atrophies too. The bones thin, through a process that resembles osteoporosis on Earth. The loss of bone dumps calcium into the blood. That can lead to kidney stones and raise the risk of depression, not to mention constipation. Astronauts exercise daily in space, but this only slows the wasting, and it is not clear how much room Tito's capsule will have for the crucial equipment.

Then there is radiation. Space is aglow with radiation from the sun, other stars and other celestial objects. There are energetic cosmic rays that zip through spaceship hulls. Dozing astronauts have reported seeing flashes of light through unopened eyes, as cosmic rays strike their retinas. The radiation takes its toll on the body, causing gradual damage to certain organs, raising the risk of cancer, and perhaps accelerating Alzheimer's disease.

Here Tito has an advantage. He is 72 years old. The background radiation he might experience on a round trip to Mars would doubtless cause damage, but this is more worrying in younger astronauts, who have most of their lives before them. There is, perhaps, an ethical argument for older people venturing out into space.

But all radiation is not alike. The more serious problem is what astrophysicists call "cosmic particle events". These include deadly blasts of radiation that are flung from the sun during a solar flare or coronal mass ejection, like this one recorded on 31 January this year. "If you are exposed to a solar flare in a thin-skinned vehicle, you are going to have a bad day in space. That sort of radiation can kill you in short fashion," says Fong. Lead lining is not practical for a small, light spaceship, but would be of questionable help anyway. On slamming into a shield, the initial pulse of radiation would spark a wave of dangerous secondary particles that flood out the other side.

Besides the physiological response to spacefaring, there are serious psychological challenges to consider. Iya Whiteley, deputy director of the Centre for Space Medicine at UCL, worked with the European Space Agency on the recent Mars500 simulated mission to the planet. "We've uncovered more than 2,000 potential issues for long duration missions, in terms of psychological, relationships and organisational issues; how they deal with superiors, their family, what kind of support they might need and what countermeasures might help them. Of those there are only a quarter we have some idea about," says Whiteley.

Her work with the European Space Agency exposed changes in behaviour that have cropped up before on space missions. There is the "third quarter effect", where motivation slumps mid-way through the long journey home. There is the "pale blue dot effect", where people experience a shift in perspective and priorities, linked with their remoteness from the world and separation from the trivialities of everyday life. As the astronauts move away from Earth, they may lose touch even more.

"They might feel that whatever their priorities – be they social, psychological, personal, interpersonal, which were connected to Earth and the society they come from – might become very distant and hard to relate to. Whatever mission control says they have to do, they might not see as necessary to do," says Whiteley.

If the mission does take a crew of two, and one of them is Tito, the duo will be united in their separation from Earth. Such long confinement with so limited company causes strains on relationships. Small quirks of character can become major problems. But far worse could happen. What if one of the crew dies mid-trip? What does the other do? What if the ship is lost, either by shooting past Mars, or impacting on its surface, as has happened with scores of Mars probes in past decades? Would that set back future international missions to the planet?

On this, Whiteley raises the unthinkable, even though I'm sure she's not serious. "It's strange to consider whether people might not want to come back," she says. "Maybe they have a plan to be the first people to disappear into space."

Tito's stated aim for his "Mission for America" is to "generate knowledge, experience and momentum for the next great era of space exploration". The nationalism in the press release provokes a little queasiness: "[The mission] is intended to encourage all Americans to believe again, in doing the hard things that make our nation great, while inspiring youth through science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education and motivation."

For all the unknowns, Whiteley is in favour of a manned mission to Mars, and would love to work with Tito on the adventure. "We are explorers. It's the natural thing for us to do if it's technologically possible. We are ready when we are ready," she says. "What is important is to send them as investigators rather than us investigating them."

No comments:

Post a Comment